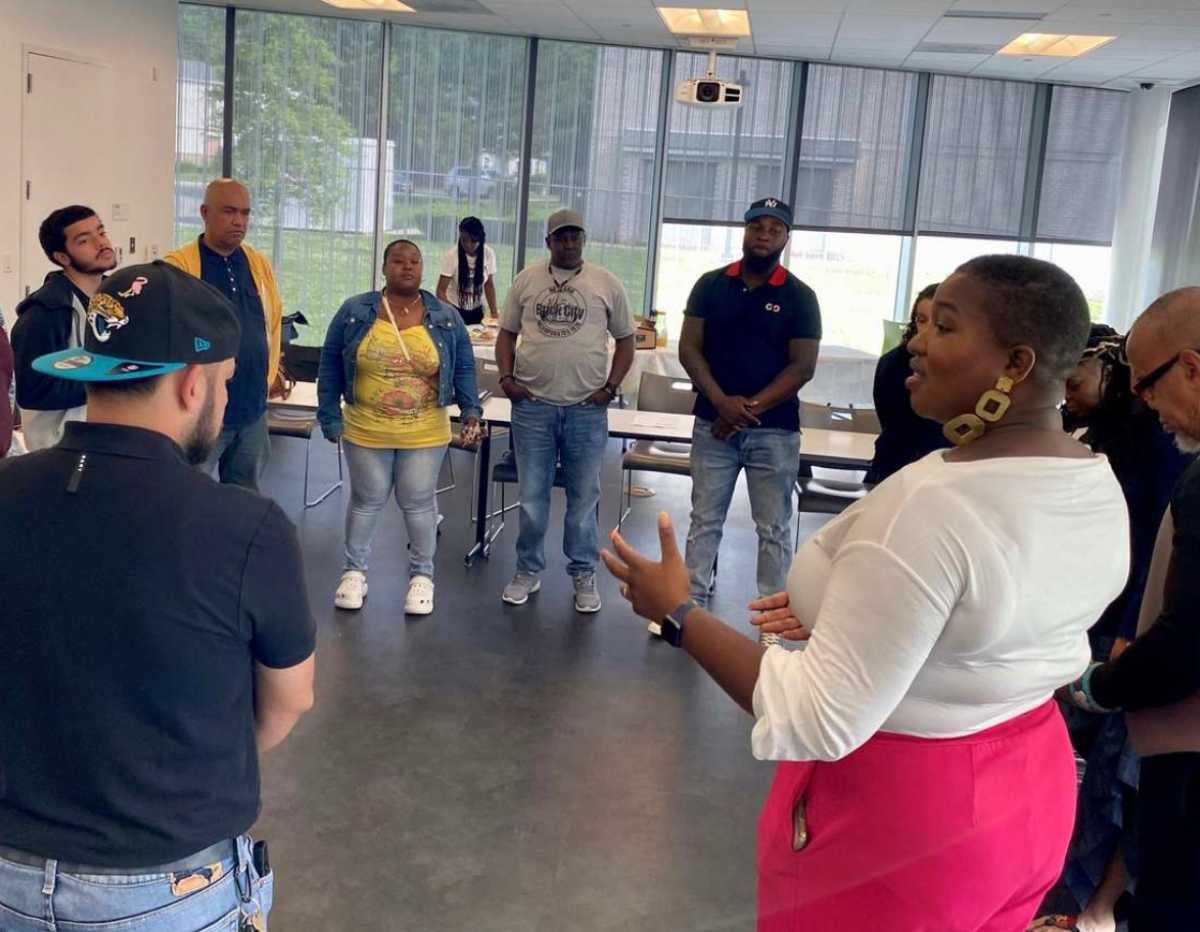

At the beginning of the summer, our executive director, Jamila Hodge, sat on a panel in a crowded gymnasium in Newark talking about transforming the justice system.

“The system is going to do what it’s going to do,” she said. “It is a machine, and it was built for a purpose, and that was to oppress and control Black people.”

As a former prosecutor, Jami knows this truth intimately. The only woman on the stage, she shared elements of her struggle to do good within the system, her complicity in perpetuating harm, and ultimately her decision to join the movement for community-centered solutions to violence. That decision, she said, starts and ends with understanding “that those closest to the problem are closest to the solution, and must be closest to power.”

The movement is and has been led by survivors, most often Black women directly impacted by violence in communities and by the violence of policing and incarceration. Two survivors and movement leaders that we can turn toward right now are Mariame Kaba and Andrea Ritchie, who recently published No More Police: A Case for Abolition, worth a read by anyone interested in the possibility of a world in which violence is rare.

No More Police was born out of decades of survivor-led community organizing and in the wake of uprisings and campaigns that arose from the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers. Black women wanted more than the failed promise of justice from our criminal legal system. “We demand more,” write Kaba and Ritchie. “Our communities deserve more. We demand transformation.”

Kaba and Ritchie begin the book with the movement history of the moment we’re in, lending their platform to Minneapolis-based organizers Miski Noor and Kandace Montgomery from Black Visions. Noor and Montgomery offer a front-row seat to the years of organizing for safety and healing in Minneapolis that created the conditions for organizations to mobilize and make sure that all of us know George Floyd’s name.

That movement history is important because it cuts through noise that #DefundThePolice was a spontaneous slogan that instantly went viral. It’s a history that Kaba and Ritchie expound, reaching back decades through flashpoints that have invited more and more people to question the idea that policing and public safety are synonymous. Ultimately, they challenge us with a more fundamental question: how do we make a world in which everyone has access to safety?

Safety is not just the absence of violence, it is the presence of well-being. Because of our years of work with communities in Newark, Baton Rouge, and across the country, we know that it takes an ecosystem of services, interventions, and institutions rooted in community, equity, and healing to create safety. While police are unquestionably connected to that ecosystem today, the questions we should ask now are 1) does the institution of policing increase or decrease safety, and 2) does policing need to be part of that ecosystem forever?

Kaba and Ritchie are clear that their answer to the first is that police contribute to violence more than they do to safety, and their answer to the second is no. The core argument in the book – that policing cannot be reformed, so it must be abolished – flows from an understanding that the criminal legal system is not broken, it’s doing exactly what it was designed to do. The violence of policing is not a flaw that can be fixed or a feature that can be minimized; violence defines both the root intention and the only set of tools available.

They write, “This is about recognizing that policing is a virulent force that must be addressed head-on—and about so much more: healing justice, transformative justice, and transformation toward a better world.” Instead of focusing on reform, we should put our creativity, time, and resources toward the community-centered safety and healing initiatives that work.

Kaba and Ritchie meticulously lay out the case that cops don’t stop violence, and in fact that has never been the purpose of policing. Police, they remind us, “are violence workers: policing, at its core, is about securing compliance through force, threat of force, or deprivation.” If our goal is to create safety, we need to start with other tools altogether. Fortunately, survivors and community-led groups have been building those tools for generations. From community-based violence intervention and prevention to mental health services, housing, and healthcare – what we would call a community-centered ecosystem – these programs and tools are effective and should be resourced.

There’s no question that this book offers provocative ideas and questions. There will be some people who will read the title and turn away. Maybe that’s okay. But if you care about public safety, if you recognize that most violence impacts Black and other marginalized communities, and if you’re tired of seeing the criminal legal system sustain the same harms that it always has, then you should consider reading No More Police.

It’s a roadmap not so much for implementing new programs, but for struggling together toward safety, healing, and equity. Each chapter is full of insights and questions, lessons and provocations, none of which are above critique. Ultimately, this book is an invitation to listen, to dream, to connect, and to experiment. Most of all, Kaba and Ritchie ask us to act, to start where we are, imagine the possibility of safety, and get to work together. The communities with whom we partner and our vision of a world in which violence is rare demand that we do just that.