The trauma of police-involved shootings and slain police officers has spurred national and local dialogue, including about racial justice, historical trauma, public safety, police accountability, and much more. This fall, EJUSA’s Trauma Advocacy Program spearheaded a new project to help facilitate even more dialogue – and develop solutions – in Newark, New Jersey.

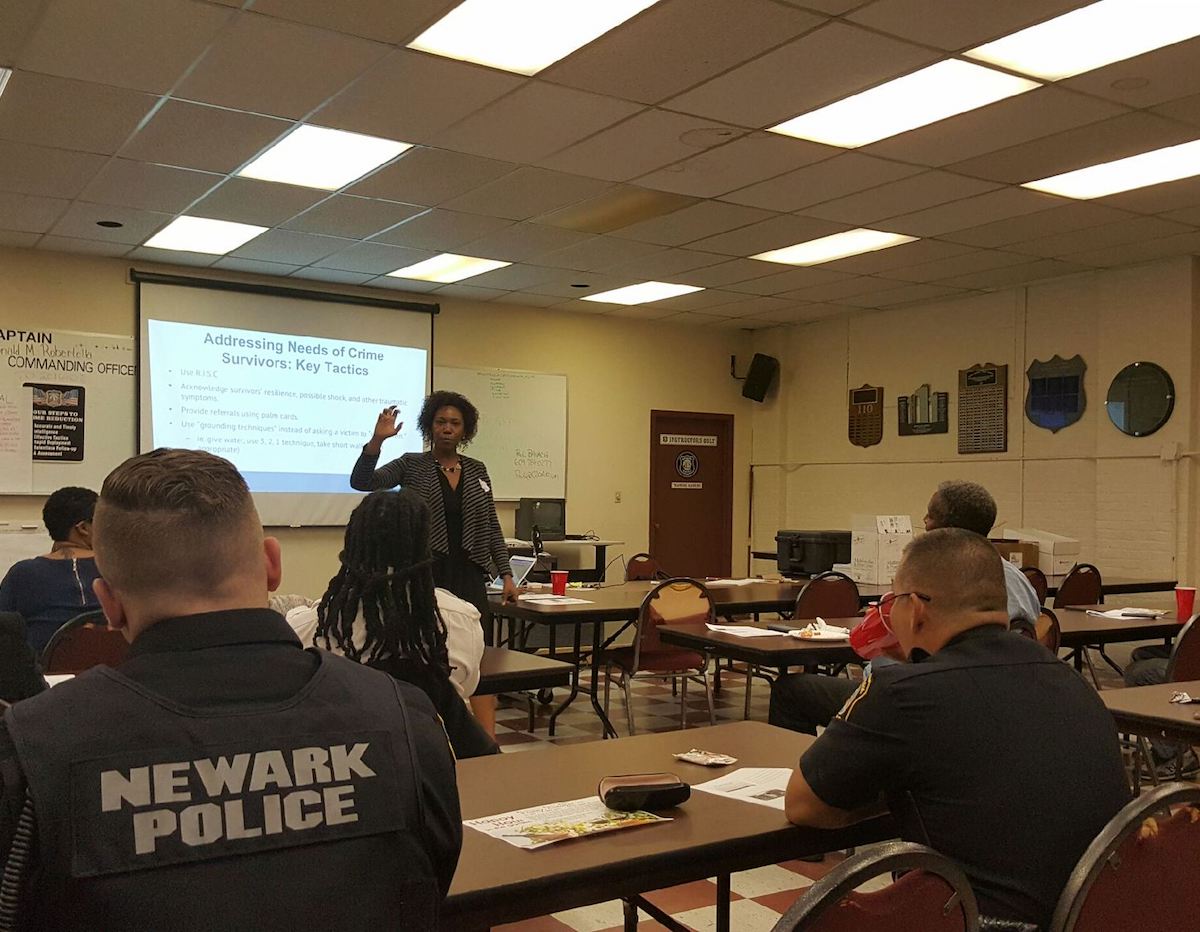

“Trauma-Informed Responses to Violence: Police/Community Training Initiative”1 has brought over 150 police officers and civilians together to learn and speak openly about their own trauma, the trauma they see around them, and the historical link between our current justice system, racial oppression, and slavery. With EJUSA staff and EJUSA-trained facilitators, small groups of 20-30 participants, police officers, residents, violence interrupters, social workers, and justice-involved citizens began to talk through the persistent obstacles to trust in the community and began the work of building mutual understanding.

The results have been deeply moving and transformative.

“What I have found most powerful about this training is its ability to allow for both police and community members to see trauma on all sides,” said Trauma Advocacy Project Director Fatimah Loren Muhammad. The idea that trauma is experienced by people throughout the criminal justice system was recently explored in a Washington Post op-ed by James E. Johnson.

EJUSA’s training2 uses trauma as a frame of analysis to surface questions of racism, trust, and ways to listen and empathize. Alongside this powerful work, participants learn trauma-informed skills that help them not only understand the link between healing trauma and reducing violence, but also to work together to reimagine the justice system.

Voices from the Training

Several officers described the trauma of responding to consecutive, horrific crime scenes. One officer shared, “I can go a few days straight seeing dead bodies. That’s just how it is. You don’t have time to process because you have to go to your next call.”

Another officer described responding to a call in which one of his own family members was nearly shot and killed. After securing the scene, he had to move on to the next call.

Civilians were shocked at the limited number of supports in place for officers who witnessed violence at such a high level. They understood and worried that, when officers experience trauma, it may impact their health as well as the use-of-force decisions they might make in the field.

Community members also shared stories about being stopped by officers and situations they found hostile. Many see a badge and fear for their lives. Some have been approached by officers with guns drawn, told by officers that their complaints are false, or routinely stopped by police.

One community member, upon sharing a personal story, concluded, “It is hard to live in a community in which the people who are supposed to keep us safe are the ones I fear.”

This message resonated with some officers, one of whom said, “I didn’t realize that my badge could be traumatizing for someone else. Just my badge. Even when I am walking to someone to offer help, it doesn’t occur to me that they could be scared.” Officers recognized that acknowledging the current and historical trauma in communities of color can go a long way in interpersonal interactions.

While individual interactions are important, the training also addressed systems. Using their understanding of trauma, officers and community members worked in teams to reimagine a trauma-informed justice system. As the teams presented, one officer deftly shared, “I have arrested some of the same young men over and over again. Prison becomes a revolving door for them. It’s just not working. I would much prefer they get some support for their trauma early on. It just makes more sense.”

At a time when the nation is grappling with the seemingly intractable issues of racism and trust among officers and communities of color, we are cautiously hopeful when we reflect on what’s possible when participants come together with courage, vulnerability, and openness to find common ground. These are the seeds of powerful, meaningful change.

A report summarizing the findings from the trainings and recommended principles of trauma-informed policing will be released in 2017.

- This training has been made possible through the generous support of the Healthcare Foundation of New Jersey and contributions from: NJ Association of Black Psychologists, Urban Renewal Corp, Newark Anti-Violence Coalition, Safer Newark Council, Violence Intervention & Prevention Specialists, Fierro Consulting, LLC, and JR Belk Consulting.

- Curriculum based on model from Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and Policy Research Associates