Kasandra Mojica earned one of two Shari Silberstein Reimagining Justice Internships in the fall 2021, working in communications. Throughout her time at EJUSA, she learned about our vision to address harm in a trauma-informed way, instead of with punishment, and she wrote this piece as a culmination of her internship. Kasandra graduated from Rutgers University in December 2021, and she plans to help transform the criminal justice system by pursuing a career in law.

All the choices I have made regarding my professional and academic career have been inspired by my cousin’s experiences with “the system.” He is just one year my elder and was raised alongside me. We even lived in the same household frequently until the age of 12. That was when he moved to an area riddled with violence and trauma. This experience inspired many of the difficult decisions that would lead to consistent interactions with the criminal legal system throughout his youth.

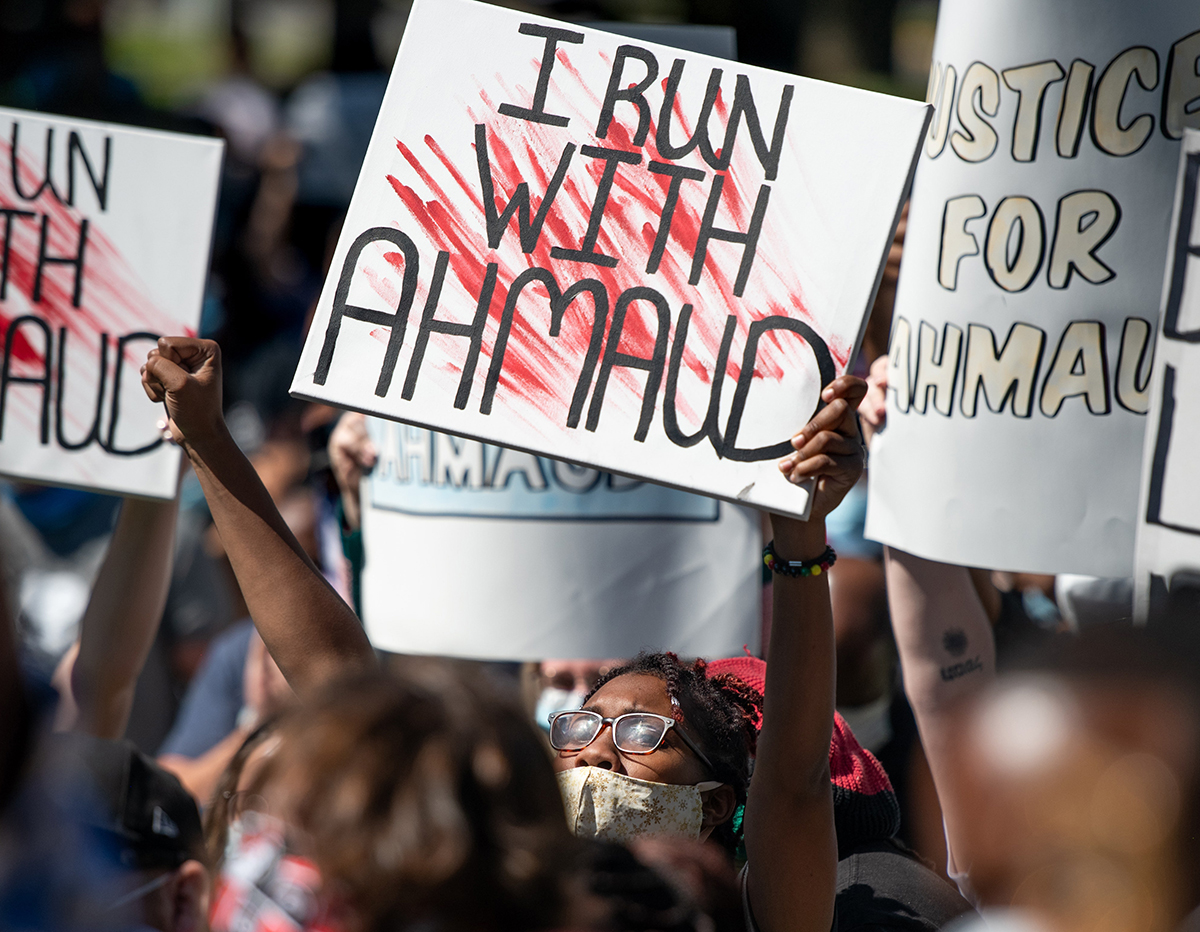

Throughout our childhood and into early adulthood, I assumed his experience was merely an unjust reality, an inherent threat that came with the territory of being a person of color in America.

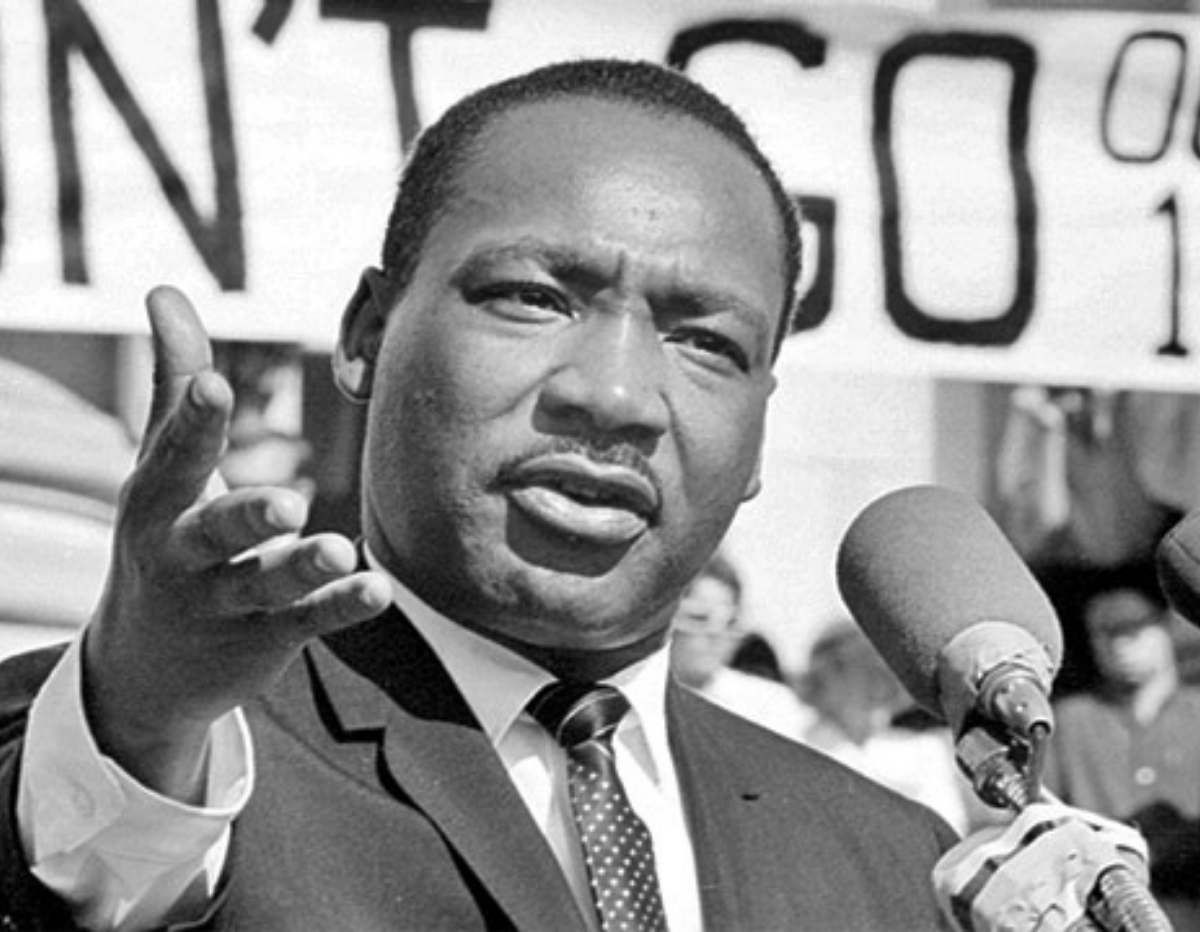

As a criminal justice major, I learned about the implications of racial profiling, concepts relating to the school-to-prison pipeline, and racial disparities fundamental to mass incarceration in the U.S. Now, I can recognize that this system was designed to produce racist results.

This January marks the eleventh month since my cousin’s incarceration. For ten months, amid a pandemic, my cousin has awaited a trial that has been consistently rescheduled.

Throughout my undergraduate career, I pursued a variety of internships to experience the impact of criminal justice. That’s what brought me to Equal Justice USA. As a Shari Silberstein Reimagining Justice Intern in communications, I was able to interact with a multitude of content concerning the legacies of racism that continue to thrive within the criminal legal system. I absorbed new insights about effective community-based programs for violence reduction and modes of healing trauma. Despite having spent three years learning about “the system” in college, it was not until this internship that I recognized the effectiveness of community-led alternatives to policing, incarceration, and other punitive measures, across the nation.

Today, the influence of my cousin’s reality, a result of the current system, manifests itself with my deep interest in the juvenile justice system and in protecting youth with similar risk factors from a similar fate. Youth issues of the criminal legal system are related to elements including but not limited to racial disparities, trauma, and family dynamics.

I live in New Jersey where, according to sentencing data released by the Juvenile Justice Commission, 65.2% of youth involved with the juvenile justice system in the state are Black, while 11.52% are white. That means that Black youth interact with the system at 5.6 times the rate of white youth. This racial disparity exemplifies the fact that racism is the rotten core of the justice system.

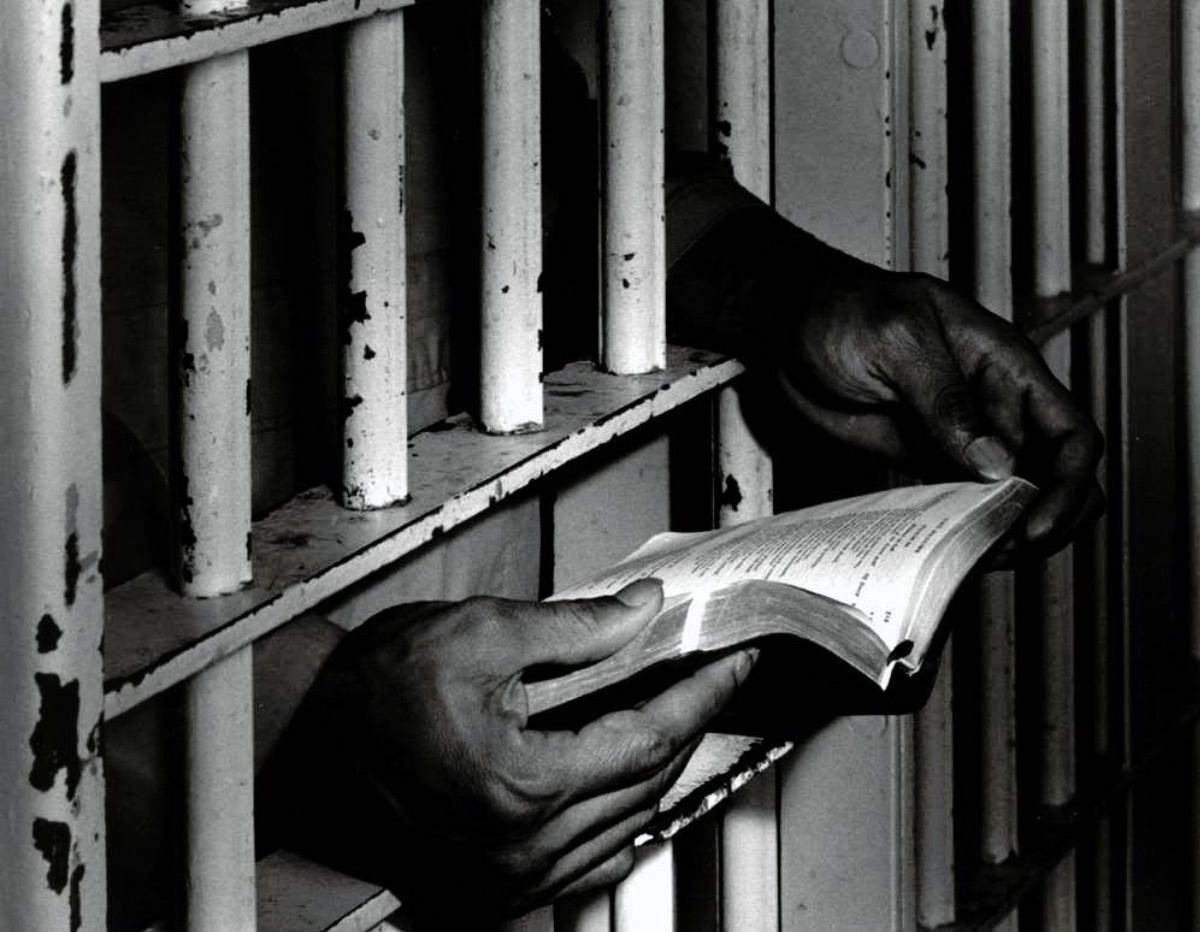

When discussing the current system, we consider the consequences of equating justice with punishment. There are so many ways to punish young people. Incarceration may be the most detrimental for youth because it separates them from family, friends, and love.

A study by criminologists Jillian Turanovic and Brea Young looked at the effect of visitation on rates of recidivism among incarcerated youth and found that “for the average juvenile, visitation is associated with a marginal reduction in the likelihood of recidivism, and that the effects are more pronounced for high-risk youth.” Although such research has proven that an increase in visitation results in a decreased prospective rate of recidivism, the prison and jail system makes regular visitation with family really hard. Reports from all over the country, in states including but not limited to Louisiana, North Carolina, and New Jersey, demonstrate the consequences of limited family visitation.

There’s no question that the removal of family support causes trauma. And trauma is almost always present before a person commits a violent act. And we also must think about the intergenerational cycles of incarceration and the effect that can have on youth before they encounter the juvenile justice system.

Was their mother or father incarcerated? How did the design of the criminal legal system hinder the relationship between the youth and their parents? Did the separation of a parent from a child damage the relationship and inflict trauma? Did the young person get any healing for that trauma? These are the questions to consider.

Inside of that, we must look at the accessibility to correctional facilities. How easy was it for the young person to communicate regularly with an incarcerated parent? The location of correctional facilities — and fees associated with phone calls, transportation, parking, and more — are all factors which could make it difficult for financially dependent children to maintain a relationship with their incarcerated parent(s).

The issues and flaws discussed above are only a few of the many within the criminal legal system as it affects youth. In proper EJUSA fashion, we must consider not only the fixes to the systems we need — we must imagine and then build the new system in its place. Project Avery is a program that has already reimagined a piece of that system. This national organization supports, provides resources for, and facilitates community among children who have incarcerated parents. The organization succeeds in addressing the trauma caused by the loss of a parent to incarceration to combat intergenerational cycles of incarceration.

Ultimately, we need a system catered to youth, that prioritizes the safety, healing, and accountability necessary to repair all instances of harm. Violence is a public health crisis, and we have all the tools to address it through solutions for our communities led by our communities in the form of violence prevention, healing, and restorative justice programs.

I believe that if we had a justice system that addressed my cousin’s trauma, and actually prevented the kind of violence that introduced him to our criminal legal system, he would not be incarcerated. He would not be awaiting a trial, after 11 months, to prove his innocence. Perhaps in another life, with different circumstances, facing a different system of justice and accountability, he would have graduated college with me just a month ago.

Today I look forward to being a part of the change to ensure that another family avoids suffering the consequences of a punitive legal system when we could have a system of true justice.