Tremane Wood, currently on death row in the Oklahoma State Penitentiary with his execution scheduled for 2025, is a grandfather, a father, a partner, a mentor, a friend, and a man who believes in second chances — not just for himself and his family, but for everyone discarded by society. He is the kind of person who speaks life into those around him, even from behind the walls of death row. There have been moments where he wrapped his arms around his grandchildren, children, mother, and girlfriend. He felt something he never thought possible: hope.

Every death penalty story is unique, but perhaps the most striking aspect of Tremane’s case is that Oklahoma plans to kill him in 2025 — even though he has never killed anyone.

Each year, the Death Penalty Information Center documents the personal histories of those executed. Between 70-100% of those executed suffer from a critical impairment: “serious mental illness; brain injury, developmental brain damage, or an IQ in the intellectually disabled range; and/or chronic serious childhood trauma, neglect, and/or abuse.”

For Tremane, it’s childhood trauma.

Tremane’s parents, Linda Wood and Raymond Gross met in the 1970s in Guthrie, Oklahoma. Linda had moved there to escape abuse in Florida and to attend Job Corp. She found work at a fast food restaurant. She was just a 16-year-old student when she met Raymond, a 28-year-old police officer. Not long after they met, Linda and Raymond started a family. They had three sons, with nicknames that Tremane had for his siblings: Andre (nickname, dreno) and Zjaiton (also known as Jake, nickname “bro”).

All three siblings grew up witnessing domestic violence within the family. Raymond’s frequent rages left their mother battered — often with broken bones and busted lips. He once held Linda at gunpoint, threatening to kill her, leaving an imprint of horror on the entire family.

By the time Tremane was eight, Linda had left Raymond, but the scars he left — on her body and her sons — remained. Despite struggling with the aftermath of trauma and a new post-traumatic disorder (PTSD) diagnosis, she fought to rebuild their lives, juggling three jobs while taking a college course.

With their mother stretched thin, the boys had too much time on their hands and too many opportunities to get into trouble. And through it all, Tremane clung to his relationship with his brother Jake, who he looked up to.

At the time, Jake struggled to find his place in the world, navigating his biracial identity in a predominantly white neighborhood. “Jake was a rebellious black sheep,” Tremane shares. As Jake wrestled with those dynamics, he introduced Tremane to guns at a young age.

The brothers, still young, found themselves on a dangerous path. One time, Tremane, Jake, and two other women decided to rob a white man, Ronnie Wipf. The situation quickly spiraled out of control, ending in Mr. Wipf’s tragic death.

Under the law, all four were charged with first-degree murder and treated as equally guilty despite their differing roles. Jake admitted to killing Mr. Wipf and received a life sentence, while the two women were given lesser sentences. But Tremane — a Black man who did not commit the murder — was sentenced to death. Reflecting on his experience at the trial, he said, “My life was on the line, and I was intimidated in court facing death row; it’s David and Goliath.”

Despite the trauma of his youth and the injustice of his conviction, Tremane remains committed to his family today. Even behind the walls of death row, often sitting 100 feet away from the death chamber, he has taken the role of patriarch, pouring into the lives of his sons, nieces, and nephews to break the cycle of trauma, pain, and violence. “When I talk to my nieces, nephews, and family, I speak life to them. I tell them, ‘Do not take your life for granted.’” For Tremane, his past is only part of the story — one that does not fully define who he is today.

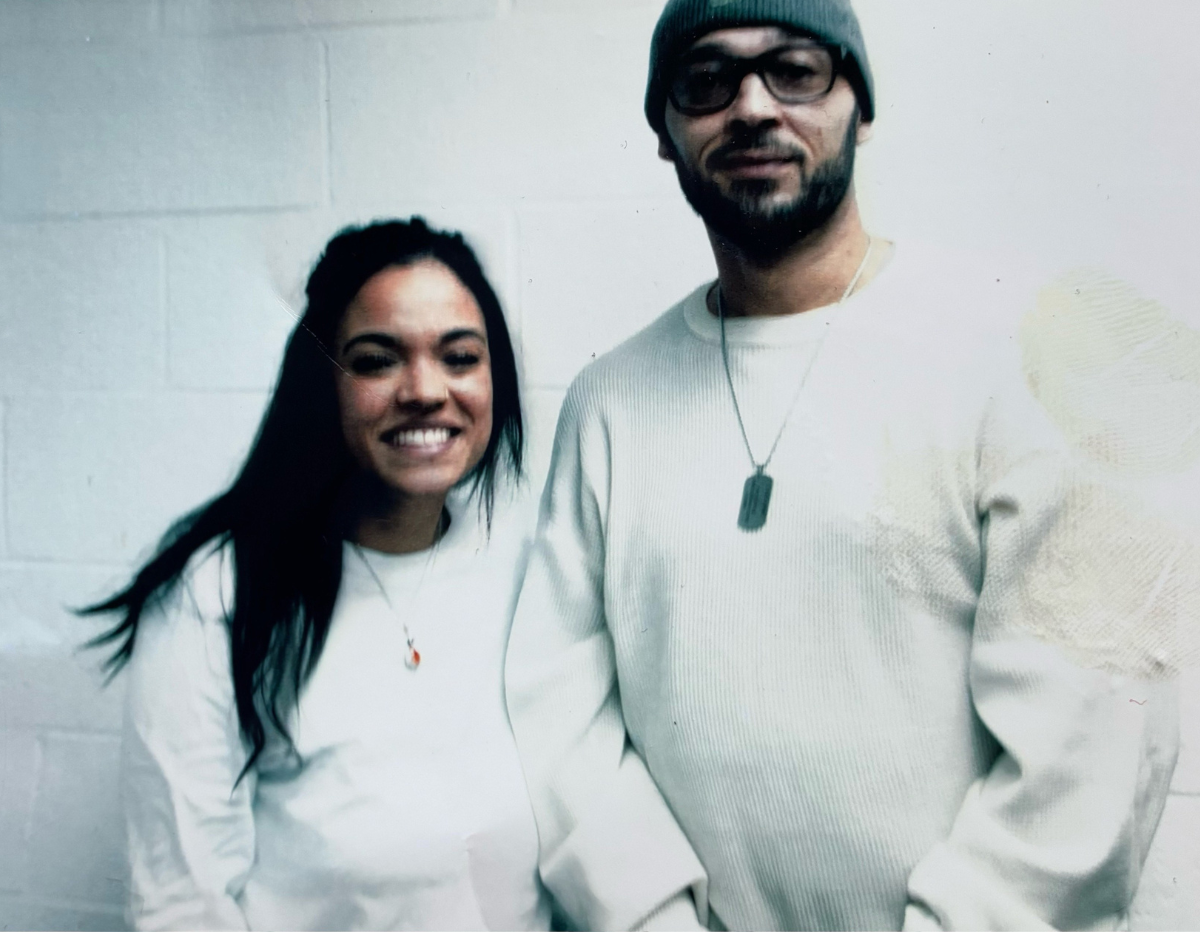

Now 45, Tremane continues to approach life with an unbreakable positive mindset. “You find strength in the strangest places. I will talk to my family,” he says. His longtime partner, Leslie, describes him as “one of the most optimistic people I’ve ever met.” She explains that their relationship is a lifeline — they write letters, share dreams, and hold onto hope for a future that remains uncertain.

Yet, even in optimism, Tremane carries the weight of the past. He often reflects on a difficult question: “How do I make up for how my bad choices at that time in my life affected so many families and lives? For what I put Arnie and the Wipfs and my family through? You can’t make up the time, but what I try to do is be positive in everyone’s life. If anyone needs me, I’m there for them. I give them words of wisdom even if I can’t be physically there.”

Leslie sees his resilience firsthand. “Despite everything, he motivates me,” she says. “His spirit, his hope — it’s remarkable.”

Leslie’s admiration reflects the depth of Tremane’s evolution, particularly in the years since his brother Jake’s death — a loss that became a turning point. “I’d been attached to my brother for so long,” Tremane reflected. “When he passed away, I felt lonely, and I began to look at myself.”

In the continued search for growth, Tremane forged connections with others on death row, including exoneree Paris Powell. “He was my big brother because my brother wasn’t here,” Tremane said. “He taught me to be a leader, not a follower.”

Leslie shared that after Jake’s passing, Tremane began to see himself in a new life. “He talks about coming into his own person since his brother passed away,” she said. No longer living in Jake’s shadow, Tremane focused on stepping outside the trauma of his family’s past, pouring energy and love into the family he has built.

As he worked to carve out his own identity, Tremane turned to books, devouring anything that would empower him — from political discourse to personal development. “He likes to be informed, and he loves conversations about politics and empowerment,” Leslie says. “It’s important to him to keep learning, to stay sharp.”

The drive for self-improvement extended into his bonds with others, especially younger men in prison. Many of them arrive disoriented and unsure of their future, but Tremane mentors them, offering advice and motivation. “Keep going,” he tells them. “You get up and put your foot forward, not six days a week, but seven days a week.”

Tremane’s self-driven motivation isn’t fueled by external validation but by his strong sense of integrity. “I feel privileged that people in the penitentiary trust me,” he said. This internal compass has earned him the trust of prison officials, who selected him to work as an assistant orderly and participate in pilot programs. It has also garnered the respect of those around him. “I find a lot of strength in helping people,” Tremane shared.

Tremane’s story does more than illustrate personal growth — it exposes the flaws in a system that prioritizes punishment over healing. His experiences reveal the deep racial and socioeconomic inequities that mark the criminal legal system.

Tremane’s journey raises difficult questions about justice and accountability. Leslie, who has stood by him through it all, reflects on his resilience with a mixture of awe and frustration. “He’s gone through so much, and yet, here he is — still fighting, still pushing forward,” she says. “But at what cost?”

Tremane’s life now, nearly two decades after receiving a death sentence, stands as a testament to the possibility of justice. Tremane’s family, friends, and loved ones describe him as a kind soul. And despite being placed in a system that seeks to respond to violence with more violence, his story suggests a different path — a path of healing, of accountability that focuses not on punishment but on growth and transformation.

What Tremane’s life reveals is a broader truth: that the death penalty system only extends the cycle of trauma and misses the chance to foster healing and genuine change. Tremane’s experience, like that of many others on death row, magnifies the racial and class inequities embedded in the criminal legal system. It also challenges the notion that justice can be found in retribution.

Leslie hopes that Tremane’s story will encourage others to rethink what accountability can look like. “He’s not just some person on death row,” she says. “He’s a father, a grandfather, a mentor. He’s human. And he’s changed.”

The question remains whether the system will allow that change to matter.

“I want to be a redemption story, especially when people see death row inmates as monsters. I want to redeem that narrative,” Tremane says.

To learn more about Tremane’s case, please read this deeply reported story from Jessica Schulberg at HuffPost, which helped inform our story. Sign the petition here to stop his execution!