I will remember this summer for many things, but three stand out: roller-coaster politics, the Olympics, and the heat. My goodness, the heat.

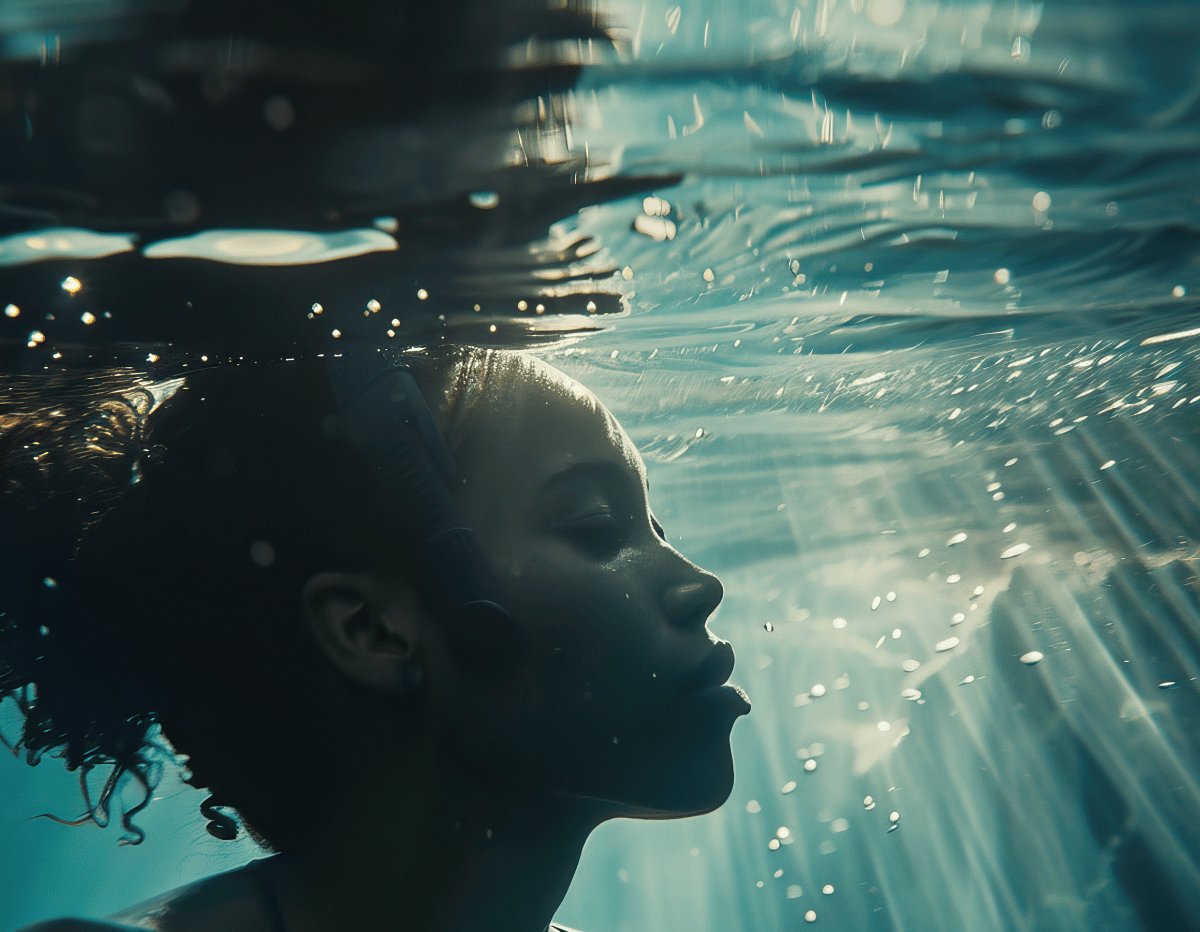

When the heat won’t quit, I want to be in the water. I grew up not far from the ocean, learned to swim in a pool at a young age, grew comfortable in the waves, and learned to spot a rip tide and avoid danger. Whether it’s saltwater or fresh, floating on top or slicing just below the surface, the water always feels restorative.

I take that comfort with the water for granted. A beautiful new mini-documentary made me realize how fortunate that experience is. Black Stroke tells the story of three Black adults in England learning to swim, overcoming fear and health concerns to do something they’ve always wanted to do.

In Great Britain, more than 85% of Black adults, youth, and children cannot swim. Here in the U.S., 64% of Black youth and children cannot swim, a figure 24% higher than white children. (USA Swimming Foundation Announces 5-10 Percent Increase in Swimming Ability, 2017)

Racial disparities don’t just happen. Not in this country. A not-new book explains a lot.

“Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pools in America” tells the fascinating stories of community pools. Cities and towns started building pools in the late 1800s, less for swimming and more for bathing. People experiencing poverty didn’t always have access to bathing facilities, so local leaders decided to step in.

These pools were located in urban areas and segregated but by gender, not race. This didn’t last, though. The first municipal pool to explicitly restrict Black access opened in 1915 in St. Louis.

Suggestion to edit: In the 1920s and 30s, pool construction increased in small towns and big cities nationwide, with literally thousands of pools. Racism played a huge role in where these pools were built and how they operated. The Highland Park Pool in Pittsburgh is a great example.

The facility – actually two pools, one a wading pool – opened in 1931. Thousands flocked to the site on opening day, including many Black residents. Officials took a page from the Jim Crow South by asking just the Black people for their “health certificates” before denying them entry.

This wouldn’t last because the city had many integrated pools. Instead, white residents and pool goers embarked on an organized campaign of violence and intimidation to keep Black residents out of the Highland Park Pool. White people would throw rocks at, punch, and violently dunk Black people, often while police officers stood by and did nothing.

This racist behavior was not restricted to one city pool; it happened all over the country. Can you imagine the trauma that would inflict? The fear and policing of swimming?

As participants in our Trauma to Trust workshop know, trauma and fear don’t exist in a vacuum. They don’t dissipate on their own. Both are passed on from one generation to another.

The harm of this is real. According to the Children’s Safety Network, Black children and youth drown at a rate nearly twice that of white children.

This is a solvable problem. We can ensure that all kids have access to swim lessons from a young age onward. We can make sure that they have access to pools nearby where they live.

Swimming is a beautiful thing. If you need a reminder, spend just 12 minutes watching Black Stroke (it’s free) to see how meaningful it can be to learn to swim, at any age. With this kind of heat, we all need the water.