The deep divide between police and communities of color in the United States can often seem intractable. But EJUSA has a long history of bridging divides that once seemed insurmountable. Our newest project to do this is the Police/Community Initiative on Trauma-Informed Responses to Violence, piloted last year in Newark, NJ. The project was profiled in a recent article, “Training Day,” a story on the role training can have in transforming police culture, anti-violence efforts, and the relationship between police departments and communities of color.

According to the article, most police training programs following 9/11 continued to militarize the police: “Officers continued to receive extensive firearm training but hardly any in psychology, conflict resolution, implicit bias, or mental illness.”

We know what’s happened since then: Michael Brown. Eric Garner. Freddie Gray. Philando Castile. Jordan Edwards. These are just some of the black men and boys who have been killed by police in recent memory. Their deaths sparked protests that caused many white Americans to realize for the first time that the safety and presumption of innocence they take for granted was not a given for their black and brown peers.

People of color, on the other hand, have long felt the pain of that difference, of fearing an institution whose stated goal is to protect. The President of the International Association of Chiefs of Police acknowledged last year that policing has long been a tool of oppression against people of color. “[T]his dark side of our shared history has created a multigenerational – almost inherited – mistrust between many communities of color and their law enforcement agencies,” he said.

This statement is part of the curriculum for EJUSA’s Police/Community Initiative, and the video always sparks a rich discussion. A key theme for many of the officers who attend our training is the frustration they feel when members of the community mistrust them or refuse to interact with them. The concept of historical trauma creates space for the officers to understand that their institutions, their uniforms – not necessarily them – represent something painful to many of the people they encounter.

“Training Day” chronicles a number of different trainings that police officers attend across the country. Most are disheartening. The first instructor profiled asks officers to reflect on mistakes they’ve made and then quickly says he’s kidding – as if the idea were comical. He believes investigators who identify civil rights violations are part of “an industry” with an “agenda”.

EJUSA’s Police/Community Initiative is an antidote to this kind of cynical, “us vs. them” vision police training. The article describes several sessions from our spring trainings:

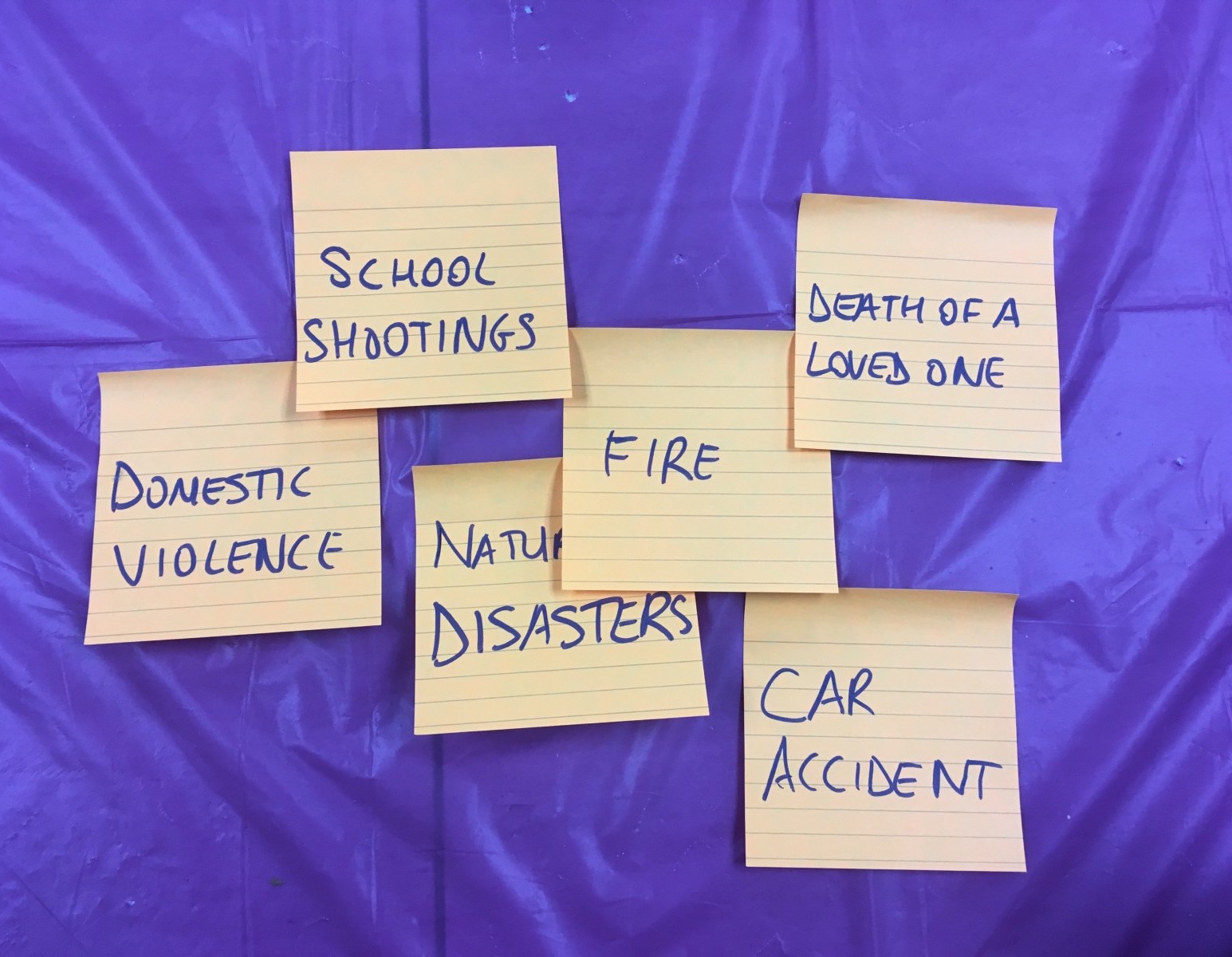

Though police officers and other first responders experience trauma on the job all the time, many of the officers in the church remain quiet during this brainstorming session. They were only sworn in four months ago, so they don’t have a lot of experience to draw on. But their commanding officer, standing in the back of the room, directly across from Swift, addresses the group. He probably qualifies for a PTSD diagnosis, he says, though at this point in his career he believes he can turn it on and off.

But sometimes he still sees the 16-year-old gunshot victim on whom he performed CPR early in his career. It doesn’t matter if he’s with his own kids — the boy’s face flashes before his eyes. Sometimes, after a traumatic event at work, he yells at his wife when he gets home.

“I was trained differently,” he says, referring to the new officers. “And I’ll admit I was trained the wrong way.” There needs to be more attention paid to the trauma officers experience at work, he says, but the resources are scarce.

…

Sometimes a group member shares a personal anecdote. One man, a community member, speaks about his sister, who has schizoaffective disorder. While dealing with police on her behalf, which happens often, he makes a point to explain her diagnosis. The police respond differently when he does this, he says, driving her to the hospital instead of treating her like a dangerous criminal.

…

During the discussion afterward, an educator at a local school admits that when the officers showed up for class that morning, wearing their new uniforms for the first time, he felt a little unsafe. “I had to fight through congratulations,” he says. But he also acknowledges that his opinion of the police has changed over the course of the training, as he got to know “these gentlemen.”

An attorney who works with domestic violence survivors speaks next. After thanking the officers for attending the training, she says she is shocked by how many wives of police officers end up in her office. Self-care is critical for cops, she reminds them, and they thank her.

To date, EJUSA has trained almost 100 police officers and even more community members. Both the Newark Police Department and residents are eager for our next round of trainings to begin in the fall. And this year we will expand the project to begin advocating for some of the changes that have emerged from the training process. We are honored to work alongside them doing this difficult and tremendously important work.

Photo Credit: Emma Freer, “Brainstorming examples of traumatic experiences”