Historian Aaron Griffith’s book God’s Law and Order: The Politics of Punishment in Evangelical America meets evangelicals at the intersection of the two vocal camps: those calling for more law and order as well as those wanting to build a justice system that heals.

This book has been rightly praised, including being honored as Christianity Today’s 2022 Best Book Award for History & Biography. A “religious history of mass incarceration,” this book is a work of both analysis and admonition.

Griffith — a member of the Advisors Group for Equal Justice USA’s Evangelical Network — argues that one “cannot understand the creation, maintenance, or reform of modern American prisons…without understanding the impact of evangelicalism.” Prisons and evangelicals intertwined themselves to both shape culture while simultaneously showing our culture for what it is, because of a belief in evangelical circles that 1) “rising crime reflected growing secularity” and 2) “state power was ultimately responsible for addressing the problem.”

The early twentieth-century progressive movement “insisted on making crime (not poverty or other social ills) the primary problem to solve.” Rather than simply criminalizing certain sins, evangelicals said that any broken law is a sin, regardless of personal trauma or systemic barriers to flourishing. Therefore, a seemingly biblical response to lawlessness is more law enforcement, something the book references and that Griffith expounds on in a separate article.

Put another way, control of behavior and conversion of the soul was prized over a compassionate consideration of what the law breaker, victims, and communities need.

Griffith calls on evangelicals to repent of “past punitive sins,” a form of conversion, since “conversions are what evangelicals do best.” This is not a cheeky turn of phrase but a genuine call for reform through repentance.

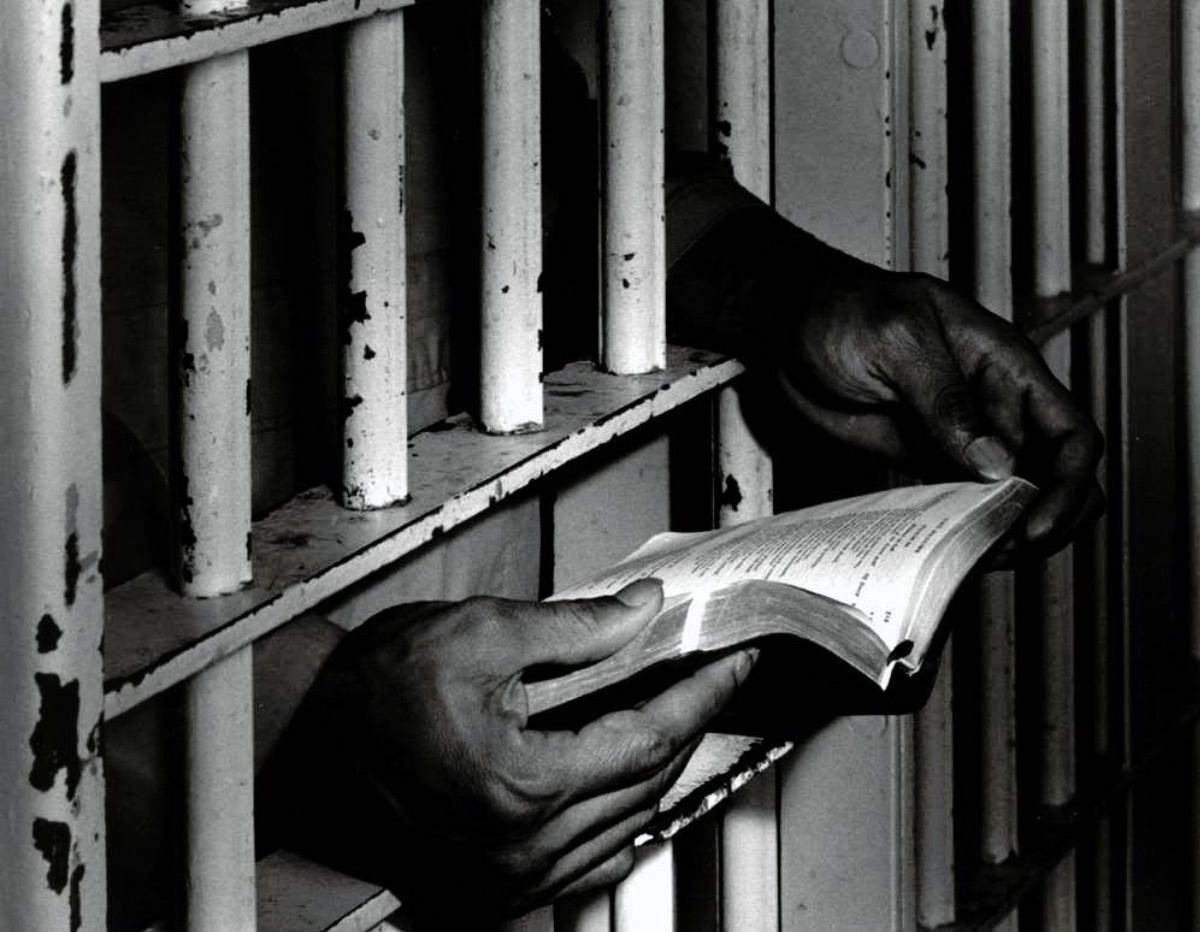

The book accurately centers the complicity of evangelicals in the development of the modern justice system while also acknowledging how evangelicals have been “pioneers in humanitarian engagement with modern prison life” through efforts like prison ministry.

Griffith’s call is for evangelicals to take that individuals-focused fervor and turn it toward a systems-focused zeal to convert a prison system into one that heals rather than one that harms.