They didn’t tackle me so much as deliver a hard body check. My phone — I was listening to a voicemail — fell to the ground but I kept my feet, off balance for a second before turning to face one of the guys mugging me.

We were under a street lamp on a normally busy Brooklyn block. The second guy stood behind me. He pressed his shoulder into my back, staying out of my view. I looked up the street toward the subway stop. People should have been coming home from work, but no one was within a few hundred yards. I was scared. I could feel my heart pounding.

The guy in front of me said, “Wallet.” I handed it over but asked him to take just the cash, that I would cancel the credit cards. He agreed but snatched my Metro card, and then my phone from the sidewalk before he and his partner walked away, calmly.

This was more than a decade before I joined EJUSA. I look back today and I’m staggered by how little I knew then about policing and prisons, about our national obsession with punishment, about violence and why it happens.

I look back today and know that these guys didn’t rob me because they were bored, looking for fun. Did they need money to buy some pizza? Did they need, or just want, new sneakers? Had they tried to find a job with no luck? Had they been mugged themselves, leaving them with the trauma of that experience?

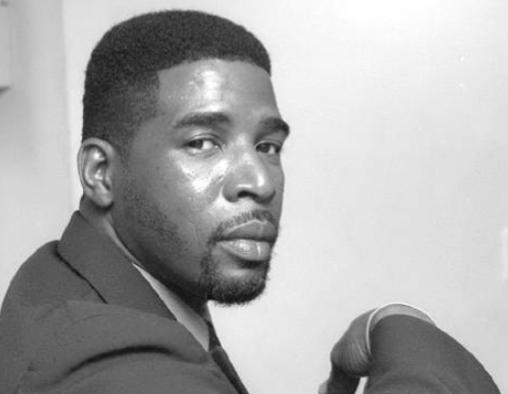

They were young and Black and living in a gentrifying neighborhood. New condos and iPhones surrounding them, but nothing coming their way.

But what I knew back then — or what I believed — is the same thing so many of us, especially white people, have been taught: If something bad happens, you find the police. So I did.

My understanding of violence and the criminal legal system has transformed over the past four years working with Equal Justice USA, having talked with many survivors and sitting with the Newark community in our Trauma to Trust program to understand how trauma manifests. I recently took another leap while reading No More Police: A Case for Abolition, by Mariame Kaba and Andrea J. Ritchie.

The book’s introduction, by two activists from Minneapolis’s Black Visions, includes this: “Criminalizing people does not solve the problems we face in our communities; it simply recategorizes and attempts to hide them.”

Two cops took a description of the kid I saw and what happened. They drove me around the neighborhood in case the guys were lingering. One cop said, “You know what you should’ve done? Clocked one of them. They never expect that.”

For a second, I felt like a coward, as if I owed something to these cops and failed, that I hadn’t seen the path to stopping this attack. But only for a second. I knew I didn’t want to hit anyone. I didn’t see meeting violence with violence as productive.

I didn’t know then that the cop’s prescription for violence is the cornerstone of our legal system. At its most extreme, we execute people who have killed. The executed are disproportionally Black people; victims are most often white. There are also countless other harmful responses to violence via policing, prosecutions, and prisons. And we have collectively come to accept those methods as so-called justice — even though they inflict so much additional harm.

The book No More Police (you can read my colleague Jiva’s summary) put me back on that Brooklyn street with those two young men, who netted $80, a cheap flip phone, and a few rides on the subway. It put me in the 77th Precinct house, rifling through a thick binder filled with photos of young Black men, and then, in the weeks following, walking down that same block at night, looking over my shoulder, scanning the sidewalks to see how many people could see me. I traveled back to an evening, weeks later, when I found those cops outside my building, with a handful of new photos, one of which showed the guy I faced under that street lamp.

I couldn’t believe it. After identifying him, I learned that he was 18 and had robbed someone else in my neighborhood.

Eventually, I would testify before a grand jury that would indict the kid. Months later, I would get a call from the DA’s office. The lawyer wanted me to know that there would be no trial, that the young man who mugged me had pleaded guilty. “What’s going to happen to him?” I asked.

“He’ll probably get two to three years.”

I didn’t know that that was possible. It took me a few seconds before I could speak. “For 80 bucks? That’s crazy.”

The lawyer asked me if I wanted to submit a statement to that effect for the sentencing. As ignorant as I was of our harmful legal system, I knew that a sentence like that was awful, that it was going to damage this guy, maybe for life. That there had to be a different way.

Yes, I did want to say that two to three years was too much.

What happened to him? I asked that question again and again as I read No More Police.

I didn’t feel safer that night long ago, as I lay awake in bed after spending hours with the cops. I didn’t feel safer after the indictment or when I found out that a Black kid might spend nine days in prison for every dollar he took from me.

Ripping him away from his family, his friends, his community, none of that addressed the possible reasons that he mugged me in the first place: that he probably didn’t have money, that he had unhealed trauma, that he wasn’t getting the education that he needed, that he didn’t have much in the way of prospects.

His life could have looked entirely different if we lived in a country that addressed the root causes of violence and provided the healing and support that people who experience trauma, and who continue to carry historical trauma, need.

But we don’t.

Now I know.