Satire. Artists of all types use it to hold a mirror up to society, maybe one of those fun house mirrors that distorts the image, makes it large, twists it around. In that redefined image, there’s a truth, one that perhaps we’re often guilty of not seeing. The mirror makes it easier for us to see, even impossible to miss.

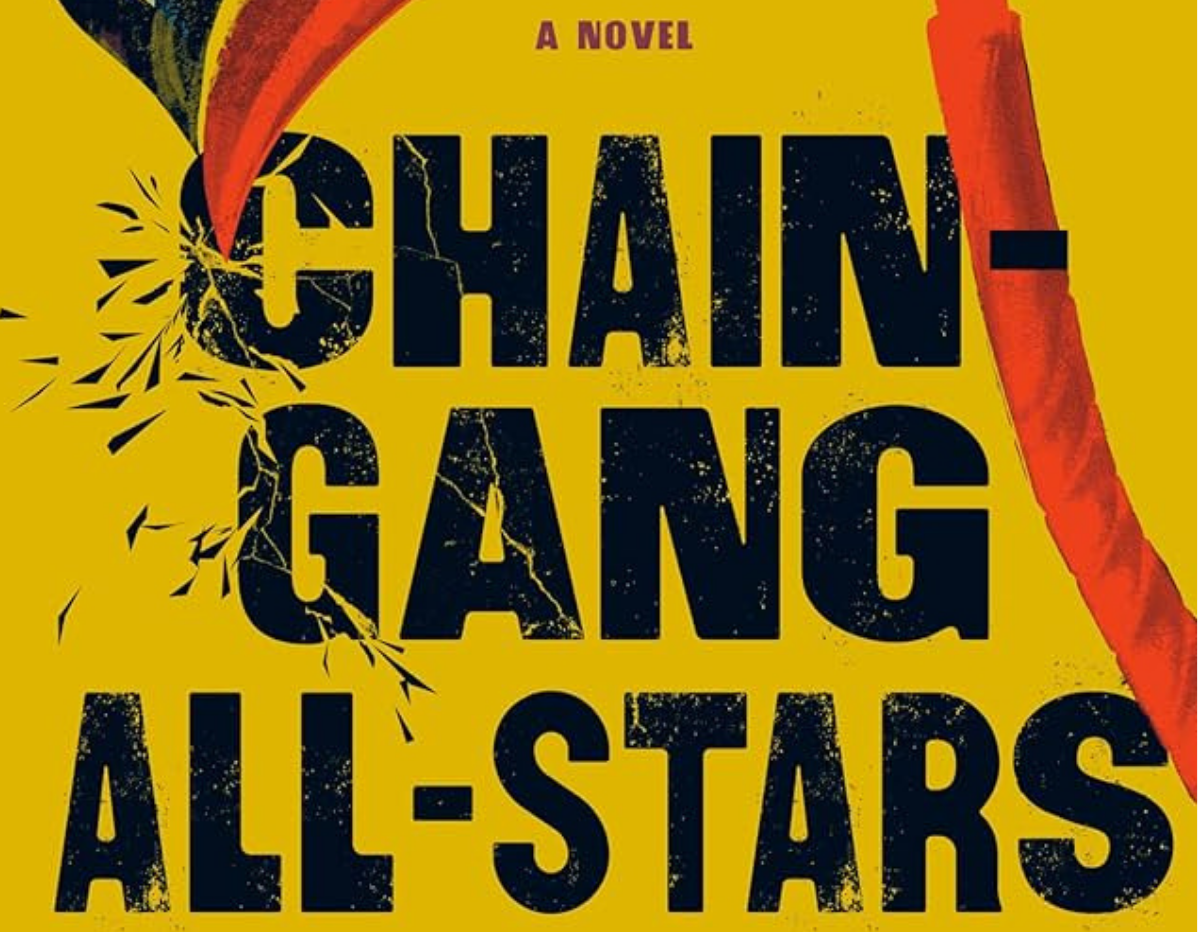

Chain-Gang All-Stars, by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, is, in my opinion, a brilliant novel. And it is a satire, capital S. Its truth is justice, and the target of its twisted image is our punishing criminal legal system.

Now, if you know EJUSA, then you know we share that same target. The system’s origins began with the establishment of slave patrols in the South and semi-organized police forces formed to protect property interests in the North. Today, we spend more than $300 billion every year on punishment and social control, and those efforts disproportionally hurt Black and Brown people, marginalized populations, and the impoverished.

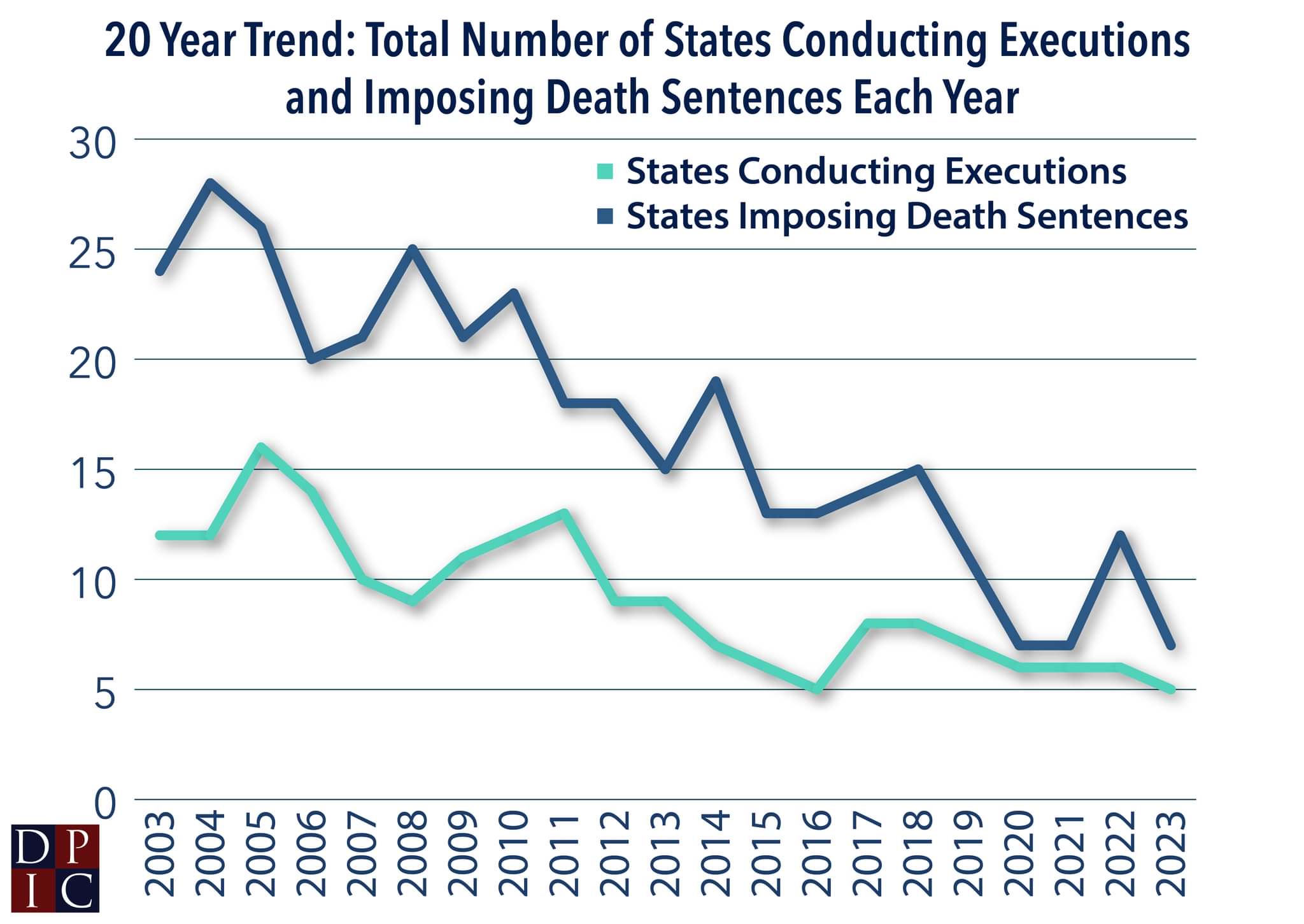

The most egregious, extreme punishments include the death penalty and, far more prevalent, death by incarceration through extensive sentences. That is where Adjei-Brenyah takes precise aim.

He imagines the Criminal Action Penal Entertainment (CAPE) program. People who have received a death or extreme sentence can, with some vetting, opt into this program that places them on teams, or Chains, that battle each other in a variety of ways. And when I say battle, the difference between a win and a loss is death. You win, you live for another day.

The carrot: win all your battles and survive for three years on the circuit, and you earn “High Freedom,” liberation. The narrative focuses on one Chain, led by Loretta Thurwar, a fierce and universally loved Link, and the last days of her journey toward High Freedom.

Loved? Yes, CAPE is televised and has become a centerpiece of American culture. And this isn’t just “sports broadcasting.” Yes, big matches take place in arenas that roar with bloodthirst. But a very imaginable reality television is available to all, the daily grind and stress of being a Link beamed into any household. Adjei-Brenyah imagines CAPE’s societal intersection in almost every direction.

But he isn’t satisfied solely with imagination. Sprinkled throughout the text are footnotes, many of which document factual information about our criminal legal system as it exists today. The story, the relationships, the action are all engrossing—and superbly written—but Adjei-Brenyah holds us to account for the system that we desperately need to dismantle.

I won’t say anything more about the stories except to say that they are filled with love and suspense, with humor and horror. And I will flag that there is violence, a fair amount but none of it gratuitous.

Given the amount of violence we see in our movies and television programs, I suspect that most of you can endure what happens in the novel. And I would hope it reminds you again that this thing so many call a justice system delivers almost nothing like it.