Imagine living in a community where children can’t play outside, morning coffee on the porch feels unsafe, and the streets are marked by violence instead of connection. For many in Bogalusa, Louisiana, this has been the reality. Yet, amidst the challenges, seeds of change began to grow with the help and determination from people like Khlilia Daniels.

Through her partnership with Equal Justice USA (EJUSA) and the formation of her nonprofit, Forever Takes a Village, Khlilia has helped transform communities. Her story, intertwined with community efforts like EJUSA’s Pathways to Healing sessions, offers a glimpse into how communities can begin to heal.

How did you learn about EJUSA?

I first encountered EJUSA on social media but wasn’t sure what they were about. I got invited to a meet-and-greet event, and a friend who was cooking asked if I could make some sweets since I used to own a bakery. I agreed and brought candy to the event.

At the meet-and-greet, I listened to Josie Alexander [our Senior Louisiana Strategist] and the EJUSA team, and everything started to click. I knew what I wanted to do but didn’t have a clear direction, and that moment made it all come together—I realized EJUSA was where I needed to be.

What did you want to accomplish for the community of Bogalusa?

At the time, Bogalusa was in turmoil. Murders and shootings happened practically every day. Kids couldn’t go outside, local parks were empty, and even sitting on your porch to drink coffee in the morning became unsafe. I had a bakery downtown, but with COVID and the violence, I had to close my doors in 2021. That August, I couldn’t host my usual back-to-school event for the kids—it had gotten that bad. You’d see certain people and know to turn around and go home because it was only a matter of time before your phone rang with news of something terrible happening.

Then, an incident at my shop happened in December of 2022, when a 15 year old was killed at my niece’s party. Everything changed. The next day, I knew exactly what I wanted to do, which was to start my own nonprofit to prevent further violence. I had always felt strongly that the name of the nonprofit needed to include ”village,” so I tried to reserve It Takes a Village with the state, but it wasn’t available. I spent hours brainstorming until I came up with Forever Takes a Village, which was accepted.

I stayed in touch with Josie and Tonjie Reese [our Learning and Practice Director] because I didn’t know who else to contact or what to do next. I told Josie, “I’m new to this—I’ll do whatever you say.” I’m genuinely grateful for their support. Fast forward to 2024, I found Forever Takes a Village, and it has blossomed, and now we’re going into year two in 2025.

How have you seen the community come together, and what has been the most impactful thing you have witnessed so far?

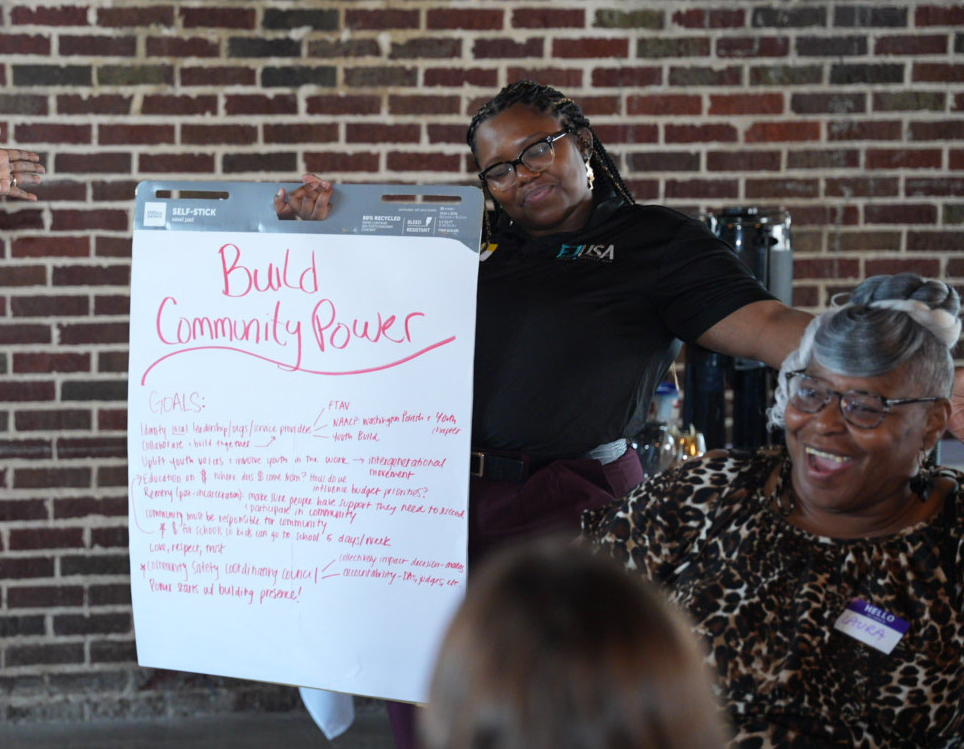

We still have a long way to go, but when Josie and the team came down to host the Pathways to Healing listening sessions, it brought the community together. People were able to speak openly and share their feelings. Some kids who typically wouldn’t say a word ended up talking by the end of the session, and we were all laughing and crying together.

After that, even though people in Bogalusa can be skeptical about things, the response was positive. People still ask if I can gather parents and kids for more sessions to talk. That was my most impactful moment—it truly helped unite this community. Some may not admit it, but that made the difference.

What do you think healing looks like in Bogalusa?

Healing in Bogalusa starts with finding truly committed people with the same mindset and vision for change. It’s not easy because, along the way, you’ll lose some people and gain others. But ultimately, it will come down to a small, dedicated handful of individuals who stick with you through it all.

There will be disagreements, but the key is learning to agree to disagree and staying focused on the bigger picture. That shared commitment and willingness to push forward together, even when things get tough, makes healing possible.

How have you personally grown in creating Forever Takes a Village?

Our town is very divided racially, and there are still many things being said that can be hurtful. I’ve had to learn to overlook the negativity. For instance, the Bogalusa Day of Action—an event where Equal Justice USA released a comprehensive report based on six listening sessions held in Bogalusa—didn’t unfold as I expected. However, I’ve learned to focus on the bigger picture instead of getting caught up in the details.

One thing that’s been eye-opening is how some of the people who were critical of me or the work in the past are now supportive. That’s the reality: people change their minds when they see the work happening. I’ve had to grow in how I react to situations like that, and I credit Josie for helping me understand that sometimes what I “want” to say isn’t what’s best for the problem.

What advice would you give to others starting their own organizations towards safety and healing?

Find people who are truly committed and share the same vision. You’ll lose some people along the way and gain new ones, but it will always be just a handful of individuals who will stick with you through it all. You may not always agree on everything, but as long as you can agree to disagree and stay focused on the mission, those are the people you want by your side.

Read the Bogalusa Report to discover the power of community-driven healing in Bogalusa, Louisiana. Local voices are leading the way toward a world where violence is rare and every community is safe and healthy.