As you’re reading this blog, I am in South Africa, celebrating something deeply special to me while keeping the inspiring life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King firmly in my heart.

Fifteen years ago, my mother began a quest to build a church building here in Reiger Park, South Africa, for a wonderful community she loved and supported just outside of Johannesburg. This was truly a grassroots effort. For years, she raised money by the dollar, leading fundraising walks, church dinners, and eventually email campaigns to engage people in her mission.

The community began using the first floor of the church building about six years ago, even with a second floor and a roof to finish. I’m so glad my mother was able to witness it because she passed away three years ago before the building was completed.

I am here with my family today for the dedication of the finished building. Just two weeks ago, we learned that our community of family, friends, and brothers and sisters in Christ raised the last funds needed to truly finish this beautiful building, every last brick, shingle, and nail.

So we are here to celebrate a journey complete.

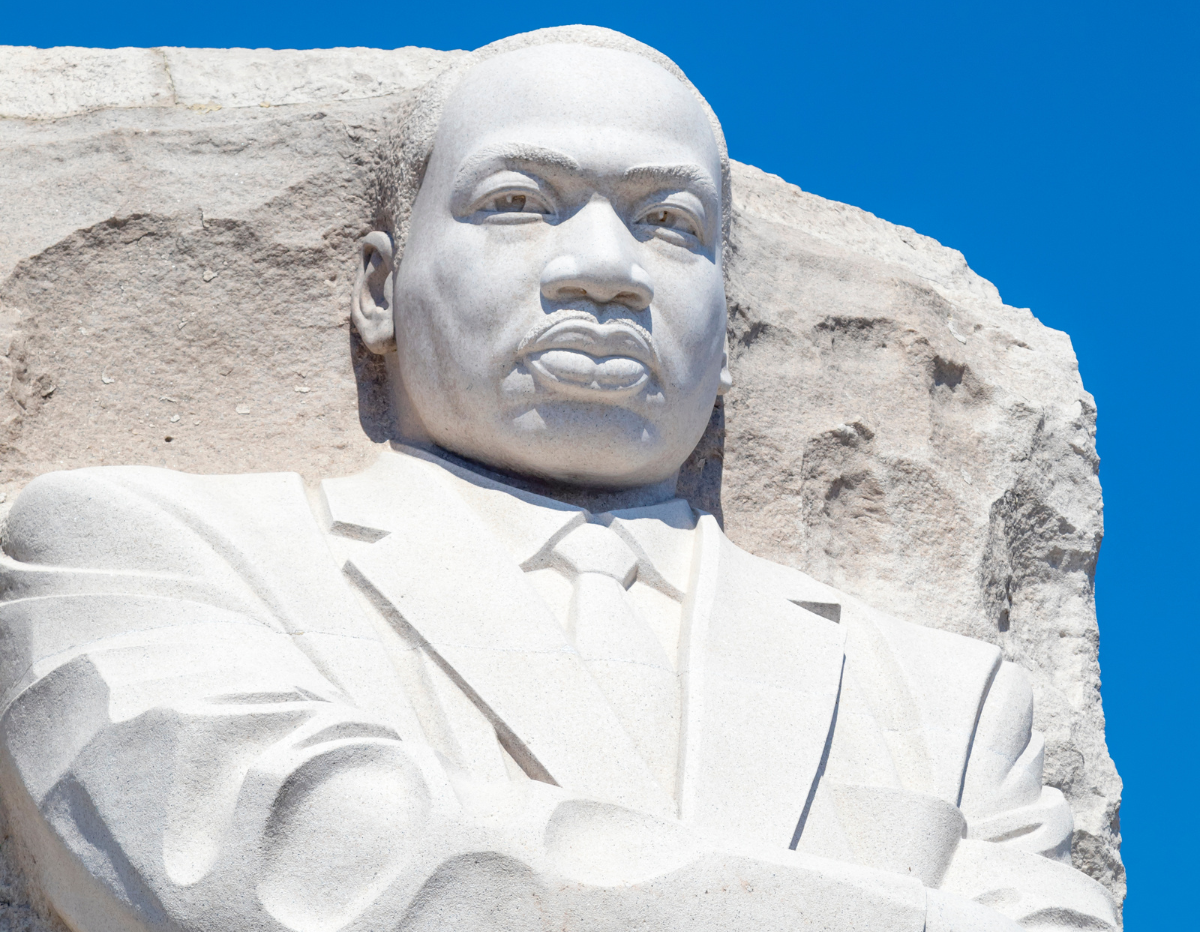

Which brings me to Dr. King.

I’ve been reading “King: A Life,” an incredible new biography by Jonathan Eig. I am amazed at how much there is still to learn about this man I’ve admired for so long. And I’m a little shaken that the building Dr. King began to build in the 1950s and 60s, through his ministry, organizing, and advocacy, is still woefully unconstructed.

In 1967, Dr. King gave a speech at Stanford University titled “The Other America,” and he cited certain facts:

- At the time, Black people had an unemployment rate twice that of white people.

- At the time, Black people’s wages were, on average, about 50% of white people’s.

- In the five years leading up to the speech, 58 civil rights activists — Black and white — had been murdered, and not a single person had been convicted.

Today? The Black unemployment rate is 5.9% versus 3% for whites. Black workers’ average wages are about 30% less than white workers. Between 2005 and approximately 2020, 98 state and local police officers had been arrested for killing someone while on duty — juries convicted only three of murder.

Writing this made me quite emotional. I feel so much joy knowing that my family and I could help finish my mother’s vision. And I feel sad that Dr. King’s vision still feels aspirational and is not a reality. As far as we think we’ve come, very little has changed.

I believe in my heart that the challenge we face is about love.

Here’s what I mean. Dr. King’s essential work centered on laws and policies. The Montgomery Bus Boycott made racial segregation on buses unconstitutional. King’s efforts drove the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act outlawing discrimination based on race, color, religion, gender, and national origin. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 then made it illegal to discriminate when it came to voting.

These victories transformed our nation. But they were prescriptive, measures that we forced upon many Americans who did not love Black people, who dehumanized and devalued them. Dr. King nodded to that, but with optimistic hope:

…although it may be true that morality cannot be legislated, behavior can be regulated. Even though it may be true that the law cannot change the heart, it can restrain the harvest. Even though it may be true that the law cannot make a man love me, it can restrain him from lynching me, and I think that’s pretty important also. And so while the law may not change the hearts of men, it can and it does change the habits of men. And when you begin to change the habits of men, pretty soon the attitudes will be changed.

More than 50 years have passed, and there are too many resistant attitudes. We needed to change hearts with intention rather than hope they will transform as a byproduct.

You know as well as I do that we still need the laws, especially because we’re seeing them unravel before our eyes. But love will be the foundation for the change we need.

I believe that if Dr. King had lived and continued his work, he would’ve seen the importance of building on love and getting to the heart of these matters. King’s legacy is so much more than the laws he passed.

At EJUSA, we use the word “build” regularly and intentionally. And building takes time, especially when you want something solid that will withstand all tests.

So I invite you today to recommit — in Dr. King’s honor — to the foundation for change, for healing, for safety and justice. And to acknowledge that when we build it through the love of all of our neighbors, we will build it to last.

Toward justice, and love,

Jami