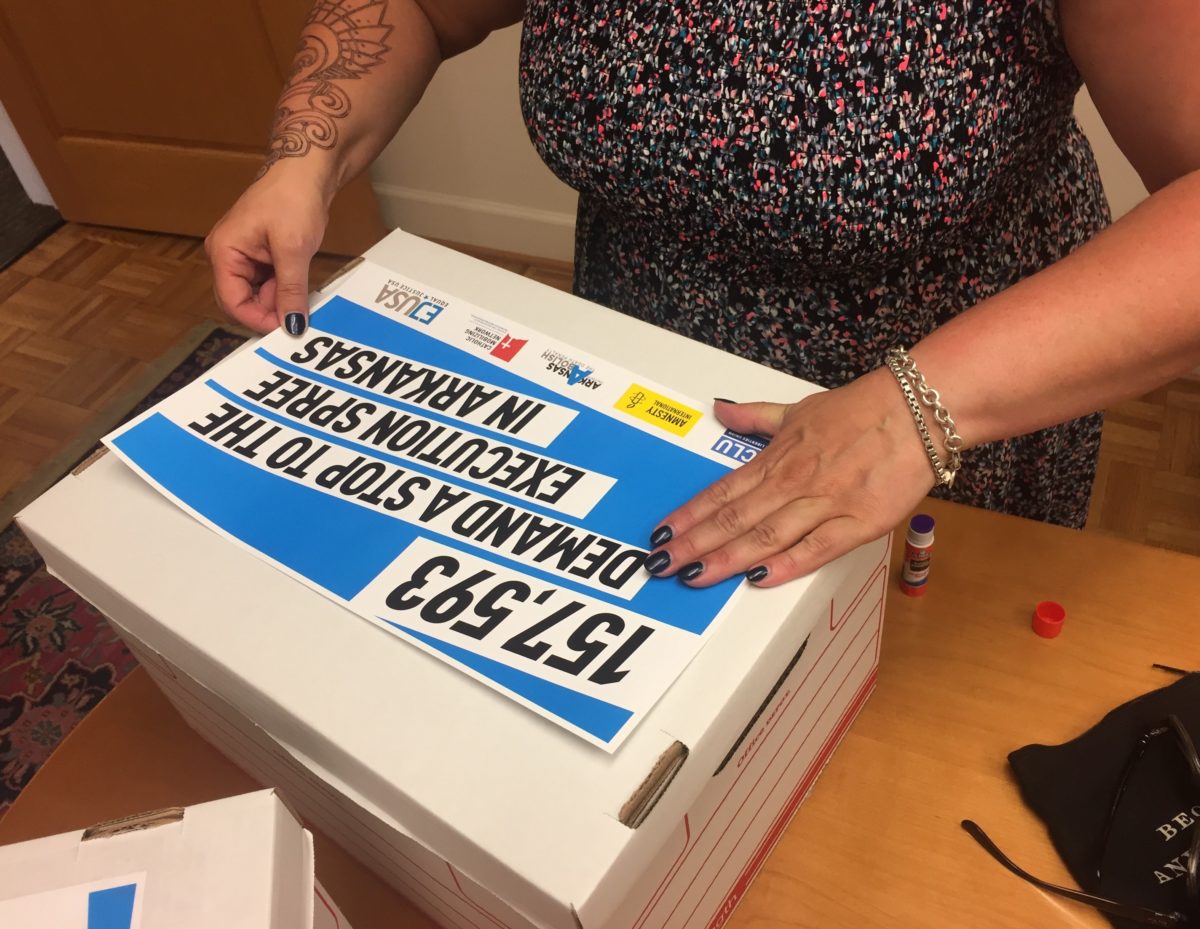

The nation’s eyes were on Arkansas as it executed four people in 10 days in April, including holding the nation’s first double execution in almost two decades. The schedule drew national outrage, including 250,000 petition signatures delivered to the governor, intervention by victims’ family members, and celebrity involvement.

Much of the attention has been on the timeline, the process, and specific problems with each case, including faulty forensics, bad lawyers, mental impairments, racial disparities, unexamined mitigation, etc. At least half of the men experienced unspeakable childhood trauma – one of many reasons to spare their lives.

But now that some of the dust has settled, it’s time to ask a deeper question than whether or not to execute. Buried in those horrific childhood histories is a more profound story that gets to the heart of our nation’s misdirected approach to violence prevention and public safety. A public health approach might very well have prevented many of these murders in the first place.

Consider the stories from among the eight men that had been slated for execution. One was routinely whipped, witnessed significant domestic violence and substance abuse, and may have been sexually abused. Another was savagely beaten by his mother with belts, boiling water, and extension cords. She started pimping him out to friends when he was just 10 years old. A third was once forced to live outside in a dog run for missing curfew, and later forced to watch while his father killed his dog, a best buddy. A fourth was abused by his father and then abducted and raped by three strangers before he twice attempted suicide. A fifth was severely abused by his mother, including covering him with tar and submerging him in ice water.

Many people experience severe childhood trauma and never go on to commit violence, exhibiting instead tremendous resilience in the face of adversity. And the trauma these men and countless others on death row experienced does not excuse their actions. It does not bring their victims back, it does not make their crimes ok, and it does not reduce or nullify the devastating pain of the murder victims’ families left behind.

But it does give us a roadmap for the future. There is strong evidence to suggest that exposure to violence and trauma, especially during critical years of child brain development, has profound impact on future behavior. This is especially true when compounded by other risk factors like chronic poverty and racism. Childhood trauma increases the risk of mental health problems, physical disease, and emotional and financial stability. It also increases the risk of future violence and justice system involvement, especially for communities of color who are more likely to be targeted by justice system interventions and less likely to be supported by healing interventions.

In other words, violence spreads. Public health experts who have long studied violence and its causes believe that violence can become much more rare. Rather than the failing of individual bad people, violence behaves just like other diseases that can either spread when treated ineffectively, or be systematically contained if treated properly.

A public health approach to violence that puts racial equity and the needs of survivors at the center could save more lives.

Imagine for a minute those men as little boys, one running naked and bleeding from the house, another banging his head against the wall to silence his demons. Imagine if these children had meaningful intervention when they were victimized so profoundly by their parents and other adults in their lives. Their victimization doesn’t undo the pain they caused others, but neither does the murders they committed undo the reality of their past trauma. Imagine they had the support and resources to heal from that horror, to become survivors and build productive lives. We would not need to debate their executions today, because their victims might still be alive.

For two weeks in April the nation focused its eyes on the circus that became Arkansas’ death penalty process. But in the long run, we have more important things to do. It is time to realize that executing or not, imprisoning or not, are the wrong questions. We already know what to do to prevent violence before it’s too late. The real question is why aren’t we doing it?