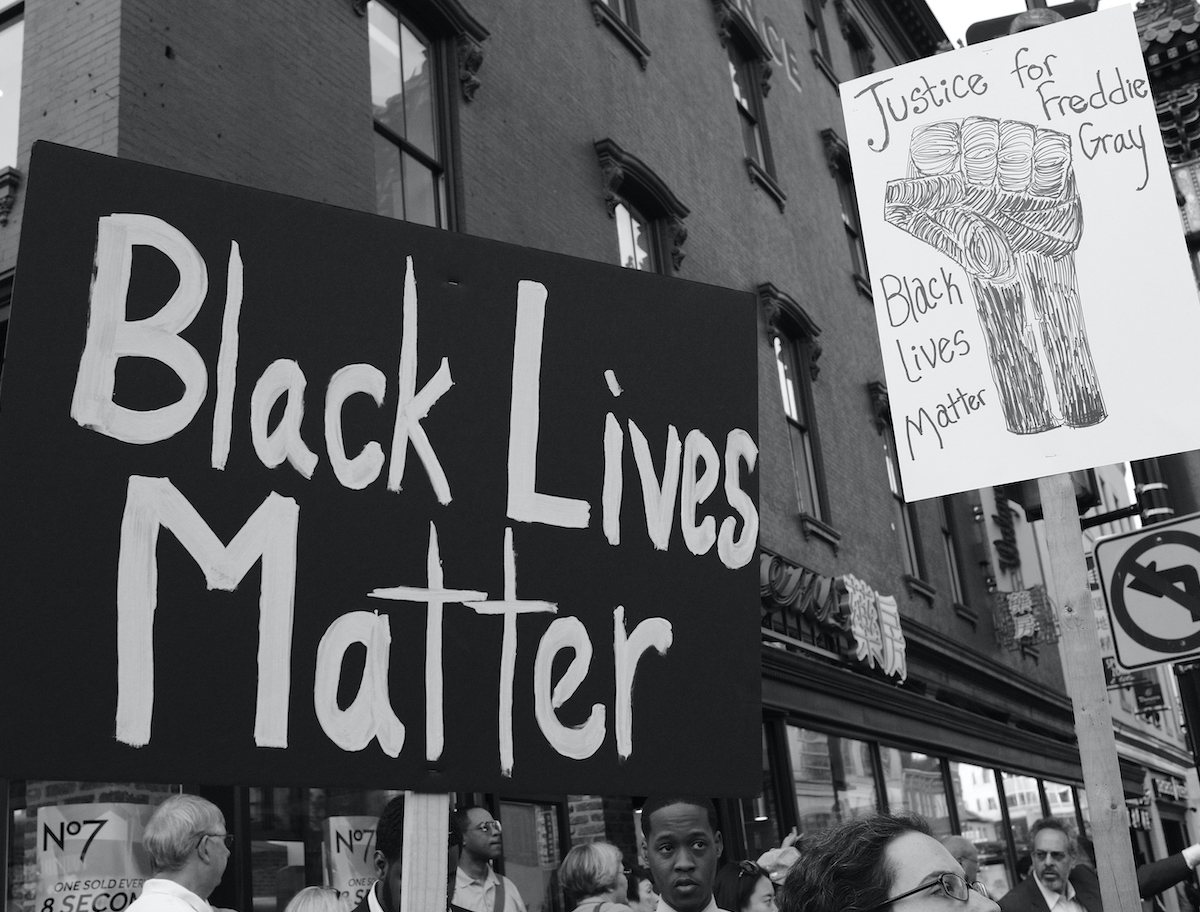

All eyes have been on Baltimore in the last few weeks following the death of Freddie Gray, a 25-year old black man who died in police custody last month. Much of the media has focused on the protests or the indictments of six police officers in the case. Others have called attention to the broader issue of police violence in the city, economic issues like jobs and housing, or Baltimore’s crime rates.

When the cameras leave, all of those important issues will need addressing. But there’s another item, rarely discussed, that also needs addressing: trauma. As a society, we wring our hands about high levels of violence in certain neighborhoods, but offer virtually nothing to those who have been harmed by it – especially when they are people of color.

Indeed, people of color – especially young black men – are more likely to be victims of violence than white people. And if you talk to people who were formerly incarcerated, you learn how so many of them were victims of violence first, never receiving any treatment for the trauma they experienced. Yet the assumption is that people who commit crime and those harmed by it are worlds apart, not only geographically but racially: the mainstream cultural trope still frequently assumes that black men commit crime and white women are its victims.

What does all this mean for Baltimore, or Freddie Gray’s neighborhood of Sandtown-Winchester, and what do we do about it?

There is a growing body of research drawing attention to the high levels of untreated trauma and PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) in cities that experience high rates of violence. Last month, Common Justice held “Paving the Way to Healing and Recovery: Conversations with Young Men of Color Who Survive Violence,” the first conference in the country focused on male crime survivors of color. Cities like Philadelphia are investing in trauma treatment as a citywide response to violence.

This conversation must get louder, backed up by a demand for more resources to treat trauma as a foundational part of our society’s response to crime and violence, including – but not limited to – violence by police. And trauma care must be available to the communities that are most likely to experience violence – including places like Sandtown-Winchester.

Today, we have an unprecedented opportunity to help make that happen. Late last year, Congress approved a significant increase in funds flowing from the Victims of Crime Act. These funds, known as “VOCA funds,” are a primary source of funding for victims’ services and compensation.

The large increase means that more federal victims services funding will be available to states than ever before. Those of us who care about justice and healing must make sure that states use those funds to close the gap, bring racial equity to victims services, and ensure that everyone impacted by violence and crime has access to trauma care.

Photo credit: “#DCFerguson Solidarity With Baltimore 10” by Stephen Melkisethian. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.