Growing up in Birmingham, Alabama, a focal point during the Civil Rights Movement, I had been to museums and monuments around the city that honor activists and organizers from the sixties. I’ve read every plaque, and I know every story where a Black person was denied access to a building during segregation.

The steps leading up to my school were the very same steps that a mob beat Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth for trying to enroll his daughters into John Herbert Phillips High School, a white school at the time.

I can give you directions to Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, point out one of A.G. Gaston’s old buildings, and recite Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” Each story, legacy, and struggle permeated my everyday life in both obvious and subtle ways.

As I got older, I became aware of the evolution of anti-Black racism over the years. The familial relation between American slavery and it’s offspring — mass incarceration, poverty, death penalty, and others — became clearer.

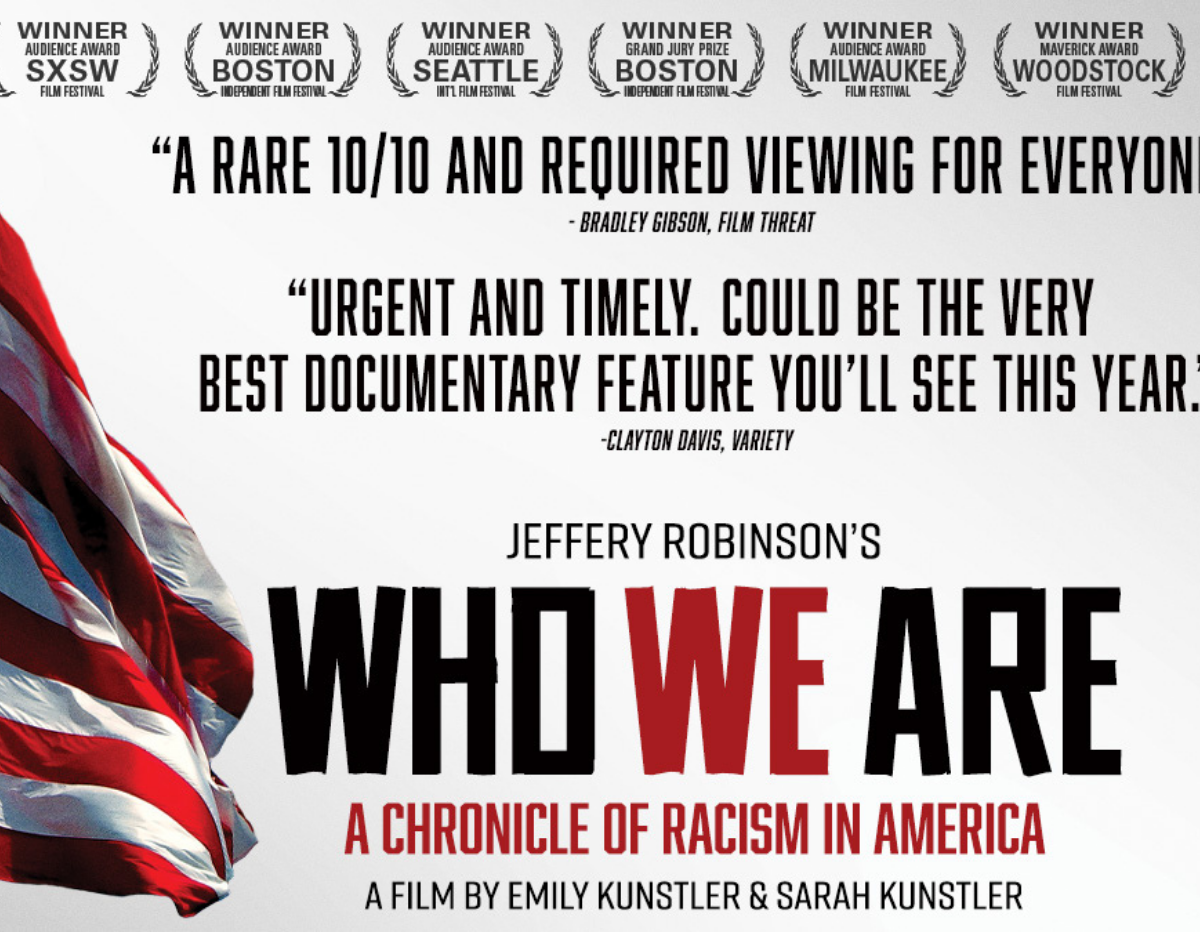

As I sat down to participate in a virtual screening of Jeffery Robinson’s Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America, I was skeptical that I would learn anything new about our country’s history of racism.

My issue was that I kept being left with the same unanswered questions. How do we reconcile what’s been going on for centuries with what people of color are still suffering from today? And, I had yet to watch anything that fully answered my questions.

The documentary opens with Robinson, the former deputy legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union, giving a lecture on Juneteenth about anti-Black racism in the U.S. The platform reminded me of a TEDTalk, so I was excited to see the visual aspects of his speech.

To reduce his lecture down to its bare bones, he argues that America, the country that we love, was founded on anti-Black racism, and the effects of that are pretty obvious.

He draws a line from Virginia laws that allowed the death of an enslaved person while resisting a master, and the death of Black people today killed while resisting arrest by a police officer.

Throughout his talk, there’s footage of him traveling to lynching sites and institutions that were built by enslaved people, showing the remnants of our racist founding.

The most troubling part of the documentary was his conversations with supporters of the confederacy. The individuals he met with were unaware of how enslaved people were treated and the true cause of the Civil War. As books and media that tell the full picture of America are banned, I fear that the gap between the truth and the people is widening.

Many of the reviews of this movie call it a necessary watch. Whenever a retelling of our history is in the form of a movie or a series, it’s called “necessary.” To their credit, the reviewers are just trying to express how much they think viewers would benefit from watching. However, every other piece that comes out on a streaming platform can be considered “necessary” or a “must watch.”

What’s the difference between Who We Are and, say, a show like Bridgerton, that is considered a “must watch”?

The thing that’s standing between us as Americans and true change, is our inability to reckon with our history. Until we do that, there will always be a block. So Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America isn’t “necessary,” it’s a step in removing that block.